Planning approvals vs housebuilding activity, 2006-2015

Daniel Bentley, August 2016

The new prime minister, Theresa May, has signalled her intention to deal with the “housing deficit” – the year-after-year shortfall in the number of homes that are built compared with the number of homes that are needed. The government’s target is to build 1 million new homes by 2020, the equivalent of 200,000 a year. Many housing economists think that England needs at least 250,000 new homes a year to keep up with demand. Neither of these targets are being met: last year (2014/15) only 155,000 new-builds were completed.

The new prime minister, Theresa May, has signalled her intention to deal with the “housing deficit” – the year-after-year shortfall in the number of homes that are built compared with the number of homes that are needed. The government’s target is to build 1 million new homes by 2020, the equivalent of 200,000 a year. Many housing economists think that England needs at least 250,000 new homes a year to keep up with demand. Neither of these targets are being met: last year (2014/15) only 155,000 new-builds were completed.

In order to tackle the shortfall it will first be necessary to correctly identify the obstacles. For many years it has been claimed that the planning system is a major barrier to progress on the grounds that it is slow and cumbersome in issuing planning permissions. This briefing note seeks to explain why this is not, in fact, the main problem today.

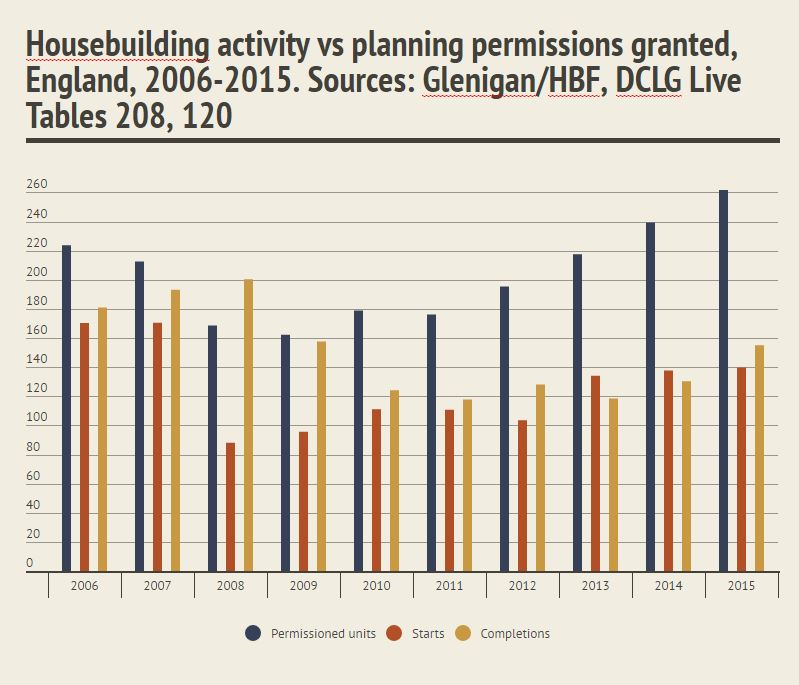

Our analysis shows that potential new homes are granted planning permission in much greater numbers than developers build them out. More units have been permissioned by planning officials than started by builders in every year for at least the past decade – and the gap has been growing ever wider in recent years. Over the past two years, planning permissions have been granted in sufficient quantities to meet a target of 250,000 a year.

This demonstrates that the key to building many more homes does not lie in increasing the number of permissions which are granted each year – although that should not be discouraged – but in ensuring that those permissions which are granted are built out much more quickly. This is likely to involve radically shifting the incentive structures which govern the behaviour of landowners and developers who are in possession of those planning permits.

The main points from the analysis are:

- Planning permission has been awarded in England for 2,035,835 housing units between 2006 and 2015. That is an average of 204,000 new homes a year – an annual rate sufficient to meet the government’s housebuilding target for this parliament of 1 million homes by 2020.

- Starts recorded by the government during the same 10-year period numbered only 1,261,350, however: an average of just 126,000 a year. This means that there have been 774,485 more permissions than starts, equivalent to 77,000 a year for the period.

- This shortfall has been growing wider over the past five years. A significant increase in the number of planning permissions granted since 2011 has not been matched by a comparable increase in starts or completions.

- In the past two years (2014 and 2015), 500,956 units have received permission, in line with the 250,000 homes a year that most housing economists think England needs as a minimum. In neither of those two years did recorded starts get above 140,000, however, little more than half of what has been approved.

- Last year (2015) there were 261,644 homes permitted for development – but just 139,680 recorded starts. This is a deficit of 121,964, the biggest by far over the 10-year period analysed and almost twice the level it was in 2010.

A ‘start’, as the term is used by the Department for Communities and Local Government in compiling its housebuilding figures, refers to the point at which work begins on laying the foundation of a new development, but not including site preparation. This means that when foundation work begins on a pair of semi-detached houses two units are counted as started; when the foundation work begins on a block of flats, all of the units in that block are counted as started.[1]

A completion is counted when the unit is ready for occupation. The number of completions for the period has been substantially higher than the number of starts: 1,506,030 between 2006 and 2015, an average of 151,000 homes a year. This is still about 50,000 units a year fewer than the number of planning permissions granted during the same period.

The Home Builders Federation disputes the accuracy of the starts data,[2] which comes from the government’s quarterly ‘House building’ series. This data series is thought to under-estimate activity somewhat. The annual ‘Net supply of housing’ data, published each November, is more comprehensive and usually revises the completions data up from the figures cited in the quarterly series. However, there is no comparable starts data in the annual series. The quarterly series remains official government data and the best guide we have to annual starts. With that health warning in mind, and in order to provide a best-case scenario to contrast with the starts data, we have included completions data from the annual series alongside in the graph above and the table below.

For most years, the completions data is not significantly different to the starts data when compared with the numbers of planning permissions coming through – which is the point of this analysis. Moreover, completions data includes figures from sites that may have been under development for many years – it is no more a reliable indicator of housebuilding activity in response to the availability of permissioned land than starts data.

Moreover, the bulk of the difference between starts and completions data across the decade can be accounted for by the fact that, when the financial crisis struck, developers continued to complete developments that were already under way while drastically cutting back the number of starts. This can be seen for the years 2008 and 2009.

It may be fairly argued that once planning approval is granted then some time is required to prepare the site before work can commence. How long that should be – and indeed how long it should be until the development is completed – is a moot point. Housebuilders themselves suggest there is a delivery time of 2-3 years between homes being granted planning permission and them coming onto the market.[3] The assumptions behind such a timeframe need greater scrutiny – it is clear that many homes can and are built out much more quickly than that, even if the majority aren’t (and many – on bigger sites – take much longer). But the data here shows that even that three-year timeframe is not being met in tens of thousands of cases. For instance, in 2012, planning permission was granted for 195,300 units – three years later, in 2015, completions had still only reached 155,000.

The discrepancy between planning permissions and starts has been often noted in the past. What is remarkable at this point in time, however, is that the gap is getting bigger not smaller. There has been a large increase in the amount of land being approved for new housing; housebuilding has picked up a little but not in proportion to the opportunity that is there. This points to a deeper problem than the availability of land which will need to be addressed if housebuilding targets are to be met.[4]

It should be noted that of the 2,035,835 permissions granted over the past decade, a sizeable portion will have expired. Usually planning permission expires if building work has not begun after three years; after that a fresh application can be made. Assuming that most if not all of these will subsequently have been granted permission again then the actual number of plots will not be as high as that 2,035,835. However, to the extent that this is the case, attention must turn then to why so many plots of land are not even being started – not to mention completed – within three years.

In defence of developers, part of the reason for this may lie in the fact that planning permission is often obtained by non-building landowners – historic landowners or land speculators, for instance, who want to be able to sell it on with consent in place. In 2012, 45 per cent of London’s unbuilt planning permissions were held by non-builders, for instance (by 2014 this had fallen but only to 32 per cent).[5] This points to landbanking in the hope of further rises in land values.

Still, the majority of permissions are held by builders and, one way or another, land ripe for new homes that the country urgently needs is not being developed as quickly as it is being approved for development. Various factors are cited by different parties in the process. But what principally governs the rate of housebuilding is what developers call ‘market absorption’; what is meant by this is the ability of the local housing market to purchase new-build homes at the price builders must achieve in order to turn the profit they require for the development to be viable. Because of the way that the land market operates, this price must usually be in line with or above the existing market rate. This leads to a drip-feed of sales which in turn slows down the building process. There are numerous studies detailing how developers do not put up homes as quickly as they can physically build them but as quickly as they can sell them – at current market prices or above. This is a complex area which demands more detailed analysis than can be offered here, but it is clear that a successful housebuilding strategy must get to grips with, and overcome, that dilemma.[6]

Conclusion

The planning system is frequently criticised for being slow and cumbersome in approving new developments. Housebuilders complain that it takes too long to obtain planning consent from local authorities and that this is undermining efforts to increase the supply of new homes. A recent investigation by The Times found that a third of major planning applications had suffered delays in the past five years.[7]

It is unlikely, however, that such delays are the major factor behind the failure to build enough homes. The number of homes approved for development has far exceeded the number of starts every year for the past decade – and the gap has been growing rapidly since 2011. The building industry casts doubt on the veracity of the starts data – but even allowing for a reasonable margin of error the overall picture is clear. So is the trend that this is getting worse not better. Even allowing for some delay between permission being granted and ‘spades in the ground’, it is clear that new housing units are being approved by planning departments in much greater numbers than homes are being built. Any strategy to secure a step-change in housebuilding output must address this discrepancy and the factors which are dictating the rate of development once planning permission is granted.

Data sources

Planning approval figures from Glenigan/HBF ‘New Housing Pipeline’ series. 2006-2008 figures exclude developments smaller than 10 units. Starts figures from DCLG Live Table 208 in the quarterly ‘House Building’ series. Completions figures from DCLG Live Table 120 in the annual ‘Net supply of housing‟’ series (the figure for 2006, not covered in the series, is the author’s estimate based on the figure in the quarterly data).

Notes

[1] ‘House Building, March Quarter, 2016’, DCLG, p.10: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/525629/House_Building_Release_Mar_Qtr_2016.pdf

[2] Last year the HBF described the quarterly starts data as its “favoured measure of house building because it provides the best indication of current activity” (‘Big jump in number of new homes started’, HBF, 15 Feb 2015: http://www.hbf.co.uk/media-centre/news/view/big-jump-in-number-of-new-homes-started/). It no longer believes these figures are robust, however, and prefers to cite the annual ‘Net supply of housing’ series now; but this does not include specific data on either starts or the respective contributions of the private sector, housing associations and councils.

[3] ‘Planning permissions granted in principle for close to 200,000 new homes a year’, HBF, 13 March 2015: http://www.hbf.co.uk/policy-activities/news/view/planning-permissions-granted-in-principle-for-close-to-200000-new-homes-a-year/

[4] The number of units gaining planning approval in the years 2006-2008 are probably under-represented in the table here because for those years the data series used did not include homes on developments of fewer than 10 units. These are unlikely to have made a significant difference in the context of this discussion, as the number of units on smaller sites like this do not normally amount to more than two or three thousand.

[5] Molior, ‘Barriers to Housing Delivery’, GLA, 2012, p.9: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Barriers%20to%20Housing%20Delivery.pdf

[6] For a discussion of this and further references, see Daniel Bentley, ‘The Housing Question: Overcoming the shortage of homes’, Civitas, March 2016, pp.29-33: http://civitas.org.uk/content/files/thehousingquestion.pdf

[7] Andrew Ellson, ‘Planning chaos leaves Tory pledge to build more homes in tatters’, The Times, 15 Aug 2016: http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/planning-chaos-leaves-tory-pledge-to-build-more-homes-in-tatters-wjhjzwhpp

About the Author

Daniel Bentley is Editorial Director at Civitas and a former journalist. His reports include ‘The Future of Private Renting: Shaping a fairer market for tenants and taxpayers’ (2015) and ‘The Housing Question: Overcoming the shortage of homes’ (2016). He can be emailed at daniel.bentley@civitas.org.uk and tweets @danielbentley.

Download PDF